There was a time when paperback horror novels were not just great in number, but they were available for purchase everywhere. It was impossible to walk through the checkout aisle of your supermarket without seeing the latest titles - and this was even before a certain fellow from Maine came along and invigorated the industry. Horror novels would routinely hit the best seller lists in hardcover, cycle through into a cheap mass market edition a year or two later (there was a longer turnaround time then), and then the last step - Hollywood. By the time the film version of the book came out, it had been drilled into the public consciousness for years. When novels like Rosemary's Baby, The Exorcist, The Other, Audrey Rose, Demon Seed, The Fury and The Entity struck gold, it was not a matter of if they would find their way onto the screen, but when. There's a reason that Spielberg's Jaws copied the design of the book jacket for its Summer 1975 debut: that image was iconic before the first ticket was sold, thanks to the paperback best seller.

There was a time when paperback horror novels were not just great in number, but they were available for purchase everywhere. It was impossible to walk through the checkout aisle of your supermarket without seeing the latest titles - and this was even before a certain fellow from Maine came along and invigorated the industry. Horror novels would routinely hit the best seller lists in hardcover, cycle through into a cheap mass market edition a year or two later (there was a longer turnaround time then), and then the last step - Hollywood. By the time the film version of the book came out, it had been drilled into the public consciousness for years. When novels like Rosemary's Baby, The Exorcist, The Other, Audrey Rose, Demon Seed, The Fury and The Entity struck gold, it was not a matter of if they would find their way onto the screen, but when. There's a reason that Spielberg's Jaws copied the design of the book jacket for its Summer 1975 debut: that image was iconic before the first ticket was sold, thanks to the paperback best seller.Stephen King entered a market primed for multi-medium success. Carrie was published by Doubleday in 1974, and while it was a modest seller, it didn't explode until Signet published a mass market softcover edition one year later, and that mysterious neon-lit profile was

ubiquitous. (You had to open up the book to the inside jacket to find out the title, and lots and lots of us did.) Brian DePalma's film version was out by 1976, and the rest, as they say, is horror history.

ubiquitous. (You had to open up the book to the inside jacket to find out the title, and lots and lots of us did.) Brian DePalma's film version was out by 1976, and the rest, as they say, is horror history.But then the publishers changed the rules. The outstanding sales for the paperback edition of Carrie - as well as Salem's Lot - demonstrated that there was an enormous public appetite for inexpensive horror novels, and publishers like Dell, Bantam, Ballantine and Avon began greenlighting titles to be sold as straight-to-mass market, or with only the feint of a hardcover release. Suddenly King was joined on the racks by a plethora of new writers: Dean Koontz, James Herbert, John Farris, Robert McCammon, Michael McDowell, John Saul, Whitley Strieber. And, in the late 70s and early 80s, the paths of publishing and Hollywood slowly diverged. The publishers were putting out far too much product for even a percentage of it to find its way to the screen, and cinemagoers were embracing non-supernatural chills, as the Slashers began their reign of terror. For those who bemoaned the screen's preoccupation with knives and nubile young things, the paperback industry was putting out as many as a half-dozen new titles every week, exploring the wide range of Horror subjects; creatures on the loose, ghosts, demonic possession, vampires, werewolves, ecological catastrophe, nature in revolt, and, yes, stalk 'n' slash. Whatever your taste in terror happened to be, there was something inexpensive between two covers waiting to satiate your hunger.

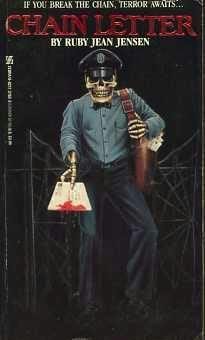

Was there a lot of dreck? Absolutely. Zebra Books saturated the market with dozens of "skull face" titles by authors like William Johnstone and Ruby Jean Jensen, books that were pilloried at the time, but I confess I look back upon them now with nostalgia. Yes, they were knocked out like so many flapjacks, but they were still Horror, and taken together with the better stuff, they allowed bookstores to feature actual Horror sections of paperbacks, and from authors whose last names started with letters other than "K." These were important if for no other reason than they allowed Horror to coexist on the racks with genres like Romance, Western, Science Fiction, and Crime & Detective.

As the Eighties became the Nineties, there was some drop-off in quantity, but every now and then there'd be a sign of renewed life (like Dell's superlative, boundary-breaking Abyss line of slipstream Horror), and it also became a challenge for adults to sift though the titles on the stands and avoid those countless books marked YA - Young Adult (although I would pronounce it "Yaaaah!"). The novels of Christopher Pike and R.L. Stine seemed to be grooming a new generation to take up the practice of perusing well-worn volumes of paperback horror at an affordable price.

But that didn't happen. The readers of such series

as Goosebumps and Fear Street did not matriculate to adult horror. In fact, they didn't matriculate to anything - they just stopped reading. As book sales faltered, paperback horror was one of the hardest-hit genres, and even established authors whose last names begin with the letter "K" saw their sales slip. Horror novels became the domain of small publishers whose titles are impossible to find at the chains, and sometimes even a challenge for Amazon to intercept. Of the two biggest chains, Borders still features a Horror section that struggles to find books from more than a handful of writers, and Barnes & Noble dissolved its Horror section years ago. (The stores in the Milwaukee area have taken to folding books with vampires, werewolves and zombies into the - shudder - Sci-Fi and Fantasy section.) Kudos must go to Dorchester Publishing and its commitment to release two titles a month by new stars like Brian Keene, Sarah Pinborough and Ray Garton, as well as established talents like Al Sarrantonio, Jack Ketchum, Rick Hautala and Ramsey Campbell.

as Goosebumps and Fear Street did not matriculate to adult horror. In fact, they didn't matriculate to anything - they just stopped reading. As book sales faltered, paperback horror was one of the hardest-hit genres, and even established authors whose last names begin with the letter "K" saw their sales slip. Horror novels became the domain of small publishers whose titles are impossible to find at the chains, and sometimes even a challenge for Amazon to intercept. Of the two biggest chains, Borders still features a Horror section that struggles to find books from more than a handful of writers, and Barnes & Noble dissolved its Horror section years ago. (The stores in the Milwaukee area have taken to folding books with vampires, werewolves and zombies into the - shudder - Sci-Fi and Fantasy section.) Kudos must go to Dorchester Publishing and its commitment to release two titles a month by new stars like Brian Keene, Sarah Pinborough and Ray Garton, as well as established talents like Al Sarrantonio, Jack Ketchum, Rick Hautala and Ramsey Campbell.The conventional wisdom is that paperback Horror collapsed under the weight of dozens and dozens of crappy books, but I don't buy that. Will that same wisdom then try to convince me that the Romance, Sci-Fi and Crime shelves are stocked with minor masterpieces? Horror used to be a reliable go-to for the traveller passing time with a page-turner while waiting for a connecting flight. It used to be an impulse buy for the shopper with a cart full of groceries. It used to be the theme for many a hardcover bestseller, later to be turned into a glossy, big-budget feature with a stellar cast. Horror fiction used to be available, dare I say it - Mainstream. It's not anymore. It's appealing to an insular, isolated audience. Success in the cinema is not pulling readers into bookstores. (It never has. Not even the phenomenon of Star Wars produced more than a temporary uptick in the popularity of published Sci-Fi in the 70s and 80s.) And with the entire publishing industry in flux, and with the future of print itself in question, it's doubtful we may ever see those days return.

How I miss coming home with a stack of paperbacks.